The Analysis and Restoration of the WPA Outbuildings in the Wissahickon Valley

Katherine Cowing, Architectural Conservator

HJGA Consulting, Architecture, & Historic Preservation

Montclair, New Jersey

Note: This article originally appeared in the publication Preserve & Play.

Figure 1. Enjoying the Wissahickon circa 1900 (Francis B. Brandt, The Wissahickon Valley: Within the City of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Corn Exchange National Bank, 1927)

During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) funded a three-phase project to improve the Wissahickon Valley in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. One of many WPA projects in Fairmount Park, this particular work included the construction of outbuildings along the Wissahickon Creek designed in the rustic style promoted at the time by the National Park Service. In 1996, after a long period of neglect and a threat of demolition, new scholarly attention demonstrated the importance of the buildings and provided recommendations for their restoration. Since then, a collaborative effort has begun between the Fairmount Park Commission and a local Friends group using this research to restore the buildings and provide them new uses.

Fairmount Park’s Wissahickon Valley, located in the northwest corner of Philadelphia, consists of 1,372 acres of steep valley walls covered with evergreen trees that edge the Wissahickon Creek. A striking landscape that has been compared to an alpine gorge, the valley was one of the first landscapes nominated as a National Natural Landmark (in 1964).(1) It is home to miles of trails for hiking, biking, and horseback riding, popular fishing spots, and many picturesque picnic areas (Figure 1). Yet the Wissahickon, known for its secluded and rural appearance, presents an anomaly: it is actually located in the midst of a major city.

The Wissahickon was acquired by Fairmount Park in 1868,(2) immediately becoming one of the park’s most beloved attractions; however, its appeal was widespread long before this time. In the nineteenth century, the Wissahickon was world renowned, some considering it in the same light as Niagara Falls. It was the subject of works by leading artists and writers such as James Peale, Currier and Ives, Fanny Kemble, and Edgar Allen Poe.(3) There were at least seven inns catering to tourists along the creek, and public transportation provided easy access for city dwellers.(4) However, despite its appeal as a natural area, the Wissahickon was not always as tranquil as it is today. Before becoming part of Fairmount Park, more than sixty mills lined the creek and a turnpike along the length of the creek enabled transportation of goods to the city.(5)

Most of the existing structures were quickly removed from Fairmount Park over the next ten years, transforming the Wissahickon into a picturesque “natural” landscape typical of late nineteenth century city parks.(6) Early in the twentieth century, after citizens protested allowing automobiles in the Wissahickon, the upper turnpike was closed and nicknamed Forbidden Drive, assuring that the park would retain its pictorial character.(7) One of the groups organized for this cause, the Friends of the Wissahickon, to this day is dedicated to the Wissahickon’s conservation and preservation.(8)

As Fairmount Park was acquiring the Wissahickon, wealthy Philadelphians began moving to the adjacent neighborhood, Chestnut Hill, and building massive stone estates. The stone, Wissahickon schist, came from a local quarry, operated by two recent immigrants from northern Italy, Augustina Marcolina and Emilio Roman.(9) The men began to coax masons to follow them, and between 1890 and 1905, more than half the population of their Italian village moved to Chestnut Hill.(10) The construction boom continued for years, forever characterizing Chestnut Hill by its Wissahickon schist buildings.

With the onset of the Great Depression, development slowed and the local stone masons found themselves out of work. The sense of social responsibility was strong in Chestnut Hill, and the established residents began creating make-work projects throughout the neighborhood. One local resident and president of the Friends of the Wissahickon, Senator George Woodward, even donated land and funded the creation of a new section of Fairmount Park. Development of the land required construction of new stone walls and an elaborate stone entry gateway.(11)

Relief organizations such as the Civil Works Administration (CWA) and the Local Works Division (LWD) also began projects in the Wissahickon. Most were landscaping projects that did not help the masons.(12) In 1935, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) took over the work of the LWD and together with the Friends of the Wissahickon built the Harper’s Meadow picnic shelter.(13) Although constructed of local stone, the shelter had a formal quality that was very different than typical park buildings.

The creation of the CWA, LWD, and WPA was very timely for Fairmount Park. In 1931, with more than 500 men working in the Wissahickon alone, the park commission considered the park to be in the best condition since it was established.(14) However, that opinion was not shared by all. At the time, Fairmount Park was criticized nationally for being old fashioned. Trends in park design had changed from romantic beauty to active recreation and Philadelphia had not kept up.(15) In 1935, Lebert Weir, the director of the National Recreation Association, completed a study of Fairmount Park and found it sorely deficient. He stated that “The Philadelphia park system is about the only great park system in the United States that has not kept pace with the wider conception of the human services.”(16) He recommended that the park commission add playing fields, swimming pools, picnic shelters, and toilet buildings, among dozens of other services that would encourage city dwellers to be active and enjoy the outdoors. Fairmount Park found the WPA a perfect instrument for modernization, and between 1935 and 1942, it used WPA labor for more than $16 million in projects.(17)

Local legend has it that the project entitled “The Improvements and Developments of the Wissahickon Valley” was started at the suggestion of one of the Friends of the Wissahickon as a small WPA project that would employ the local stone masons.(18) Apparently, the park commission believed that the initial plan was too modest and proposed a massive three-phased project intended to transform the “natural” wilderness area into a recreational prize. The proposal submitted to the WPA included improvements to the picnic areas, repairs to the fences, new recreational facilities such as tennis courts and backstops, and the construction of toilets and shelters. The specific description of work on phase one alone requested:

Improvement and Development of the Wissahickon Valley. Building 10 picnic areas, establishing lawn areas, 12 toilets, 12 shelters, 4 large shelters, planting 1,168 trees, 10,000 plants, quarrying, repair 3 dams, 6,000 cy masonry, bldg. 200 rest seats and 80 rustic benches, seeding and installing waterline for golf course, 14,675 feet cable safety fences, 600 picnic benches, redressing footwalks and baseball fields, 16,000 feet of bridle paths with 12 rustic bridges, 439 cy stone retaining walls, 6 tennis courts, 3 baseball backstops, repairing of 9,950 feet of fence and building 10,356 feet of new fence. Exclusive of any other project specifically approved or applied for.(19)

The massive proposal included work for 1,003 men on relief and 28 non-relief men for ten months. The enormity of the endeavor is reflected most vividly in the total cost, estimated to be $833,869. This first portion of the Wissahickon Valley improvements was approved by the WPA on 28 August 1937, but work did not begin until November and then not without controversy.(20)

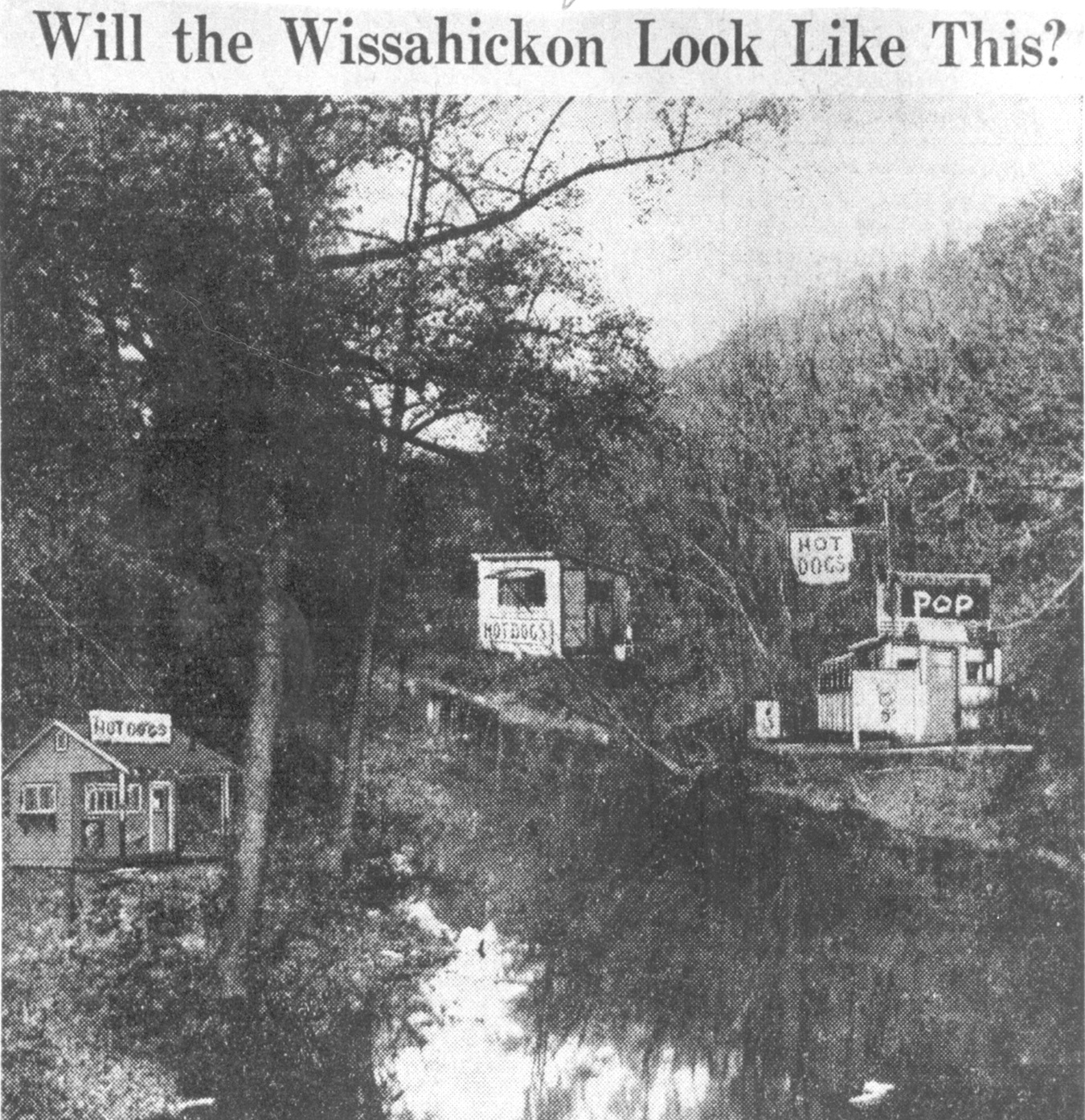

Figure 2. “Hot Dog Stand Menace Looms in the Wissahickon” (Philadelphia Inquirer, 11 November 1937. Reprinted with permission from Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

When word of the size of the project was released to the public in October, it created an uproar. The idea that the WPA would ruin the natural wonderland created sixty years prior horrified the neighbors. Newspapers published scathing articles about the park’s plan to commercialize the Wissahickon with titles such as “Cool on Hot Dog Stands in the Wissahickon” and “Hot Dog Stand Menace Looms in the Wissahickon.” (Figure 2) The project was referred to as creating an “amusement park.” Senator George Woodward was quoted as stating simply, “I think the plans are rotten,” while Judge McDevitt representing the Saddlehorse Association went so far as to describe it as “sacrilegious and disgraceful.”(21) In early November, Senator Woodward wrote a letter to the chief executive of the WPA, Harry Hopkins.(22) Although Hopkins claimed to have little influence, shortly afterwards federal landscape architects reviewed the project, and on 12 November, the WPA and the park held a public meeting to display the plans and models of a much scaled down project.(23) Six days after this meeting, the project was formally approved to construct three guard shelters, three toilet buildings, three picnic shelters, two trailhead structures, and to adaptively reuse two remaining mill outbuildings.

The Wissahickon campaigns ended only when the WPA was phased out of the park and closed down entirely due to increased private sector employment opportunities. From the beginning of the first phase of the Wissahickon Valley Improvements project until 31 March 1943, when the Fairmount Park WPA forces disbanded, not a single day went by without work on these projects. The first phase ran from 1937 to 1939, the second phase from 1939 to 1941, and the final phase from 1941 to 1943.(24) Although each phase of the project included recreational facilities, trail improvements, and the construction of some shelters, the first phase saw the largest extent of architectural construction. By the end of 1938, two buildings had been renovated and nine new buildings completed.(25) Eventually, a total of thirteen new buildings were added to the valley.

Figure 3. Allen’s Lane Shelter, original WPA documentation photograph, 1938 (Fairmount Park Commission Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).

The buildings were all of similar construction. The structures were designed around National Park Service guidelines contained in Park and Recreational Structures.(26) First published in 1935, this guide describes design standards for park buildings and was a leading force in the design of rustic park buildings so prolific in national and state parks. Several aspects of the Wissahickon structures were noticeably influenced by the NPS guidelines: 1) the buildings were constructed at the site of existing buildings or clearings so as not to disrupt the landscape any more than necessary; 2) the trail head buildings were uniquely designed to mark the beginning and end of the park; 3) the toilet buildings had horizontal clay pipes in place of windows for a combination of light and ventilation; 4) all of the buildings were constructed of stone and wood directly from the valley; and 5) probably most prominently, all buildings had a rustic motif now referred to as Parkitecture. These structures were designed to blend into the surrounding environment so they could be easily overlooked.(27)

All of the guard shelters were located between the creek and Forbidden Drive (Figure 3). They were used by the Fairmount Park Guards, the police force dedicated to the park, and as places for park users to rest and enjoy the creek. Each shelter had an accompanying toilet building hidden in the woods on the opposite side of the drive. The toilet shelters were constructed entirely of Wissahickon schist. One small picnic shelter was constructed in a clearing next to the creek and the other two were constructed at the top of the hill, serving the adjacent baseball fields and golf course. These two shelters were larger and had fireplaces and attached toilet rooms. A large trailhead building was constructed closest to downtown at what could be considered the beginning of the trail (Figure 4). It had a bicycle rental shop as well as a guard shelter and toilet rooms. The other trailhead building, marking the end of the trail, looked like a tiny, one-room western fort.

Figure 4. The Lincoln Drive Shelter (“The New Bicycle Concession Building” Evening Bulletin, 25 June 1940. Circulating collection, Wissahickon Valley, Free Library Prints and Pictures Room, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Reprinted with permission from Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).

Except for the toilet shelters, all of the buildings had a stone base with traditional log construction above. The roofs were wood shingle and the chimneys were stone. The gable ends were clad in deckled siding to represent log construction. Each guard house had an open porch and an enclosed room. The interior walls were sheathed in vertical wood cladding and were equipped with a wood stove and a telephone.(28)

After construction, the buildings blended into the surrounding landscape—so perfectly that they were soon all but forgotten. The Fairmount Park Guards were disbanded in the early 1970s and the toilet buildings were locked shortly after. By 1996, the buildings had been largely ignored for at least twenty years and were quickly deteriorating. A battle began among fans of the Wissahickon. One faction hoped to repair the buildings and the other wanted them torn down, believing them an intrusion on the natural beauty of the valley.

The repair campaign was led by Ed Stainton of the Friends of the Wissahickon and Chris Palmer, the Fairmount Park Wissahickon district manager. At the time, the WPA’s work in Fairmount Park was not commonly thought of as historic. Based on this fundamental lack of understanding about the buildings, the strategy was to repair rather than restore; using modern building techniques and materials such as dimensional lumber and asphalt shingle roofs.

During this time, the author was researching these buildings for her graduate thesis in Historic Preservation at the University of Pennsylvania and was able to locate and map each structure, based on archival records, oral interviews with elderly members of the Friends involved in the original planning, and by exploring the Wissahickon on foot. In the forty years since construction, four buildings had been lost. A standard inventory form was developed to document each building, including the location, a description, the general condition, and photographs of each facade. A summary and location of archival documentation that included the original drawings and photographs was also listed.

Figure 5. Allen’s Lane guard shelter, 1996 (K. Cowing).

Next, one prototypical building was chosen to receive a detailed condition survey and treatment recommendations. The subject building was the Allen’s Lane guard shelter. Because the buildings have similar locations and identical building materials, these recommendations could be generally applicable to all of the buildings. A graphic condition survey was completed which included photographic documentation showing the building’s current status. The Allen’s Lane shelter was hidden in the bushes and had holes in the roof; some areas of the walls and roof had significant rot (Figure 5). The stoves, telephones, doors, and windows were gone. The interior was damaged by graffiti carved into the wood.

The general recommendations established for the building’s restoration explained the practice of preserving as much material as possible and utilizing techniques that were reversible. The details for replacement of wood logs were developed directly from the original drawings; a mortar analysis provided a formula for repointing mortar; and general methods of repair were discussed. A maintenance schedule was also provided. Copies of the author’s completed thesis were provided as a courtesy to Chris Palmer and Ed Stainton. After learning the history of the outbuildings presented in the thesis, Palmer and Stainton changed their focus from repair to preservation. The threat of repair with modern building materials no longer loomed.

Figure 6. Allen’s Lane guard shelter volunteers, 1997 (Ed Stainton).

Palmer and Stainton developed a collaboration between the Friends and the park commission to preserve and restore the buildings. The Allen’s Lane shelter was the first project to be undertaken (Figure 6). The Friends provided volunteer labor and most of the financing. The park provided managing support, some financing, and some labor. The volunteers paid close attention to the tenets of preservation, including preserving as much original material as possible. Traditional log construction was to be utilized and the original construction detailing was to be matched. The workers devised a replacement window that mimicked the original detail; however, the muntins were made of metal to serve as window guards. They also installed reproduction log benches and have recently begun to mill the wood from the valley on-site using a portable sawmill. As of the spring of 2005, the Friends have completed the restoration of three guard shelters, one toilet building, one picnic shelter, one rehabilitated mill building, and one trailhead building (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Allen’s Lane guard shelter, 2005 (K. Cowing).

A second component of the Friends’ mission is to find uses for each building. They made one of the guard shelters available to a local group that provides trail maps and organizes hikes. Another guard shelter was restored to its period appearance, including the return of a wood stove and telephone. One of the old mill buildings is used as the storage shelter for the restoration materials. Currently the Friends are investigating the use of composting toilets. This has been one of the most active collaborations between Fairmount Park and a local Friends group. The restoration of the WPA structures has established a whole new status for the Friends. They have become dedicated to the maintenance of the buildings and are now involved in the planning of all projects within the Wissahickon.

WPA-built outbuildings fulfilled the need for human comfort in the parks, while responding to the picturesque quality of the surroundings. The buildings were designed in the rustic style prevalent with the National Park Service to blend into their environment, to be forgotten. This goal was so well accomplished that they were close to ruin before any attention was paid. The Friends of the Wissahickon championed the cause of repairing these little buildings when others were rallying for their demolition. Through collaboration of the Friends and the Fairmount Park Commission, nine of the original thirteen buildings will be restored and given a use. The restoration of these buildings has established a new method through which Fairmount Park can manage its tremendous resources.

Katherine Cowing is an architectural conservator with HJGA Consulting, Architecture & Historic Preservation in Montclair, New Jersey. Ms. Cowing manages the preservation and restoration of a wide variety of historic structures ranging from small park structures and railroad stations to farm buildings and large government complexes. Having received a Master of Science in Historic Preservation with a concentration in Conservation from the University of Pennsylvania, her professional pursuits have focused on developing sensitive approaches to the conservation of historic building materials.

This article originally appeared in Preserve & Play.

Notes

1. T.A. Daly, The Wissahickon (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Garden Club of Philadelphia, 1922), 9; letter of Acknowledgment from the Department of Interior to the Fairmount Park Commission, 17 March 1964. “Wissahickon Folder,” Fairmount Park Commission Archives.

2. The Fairmount Park Commission, a city agency, began by buying the Lemon Hill and Sedgeley estates along the Schuylkill River in 1867 and then rapidly expanding the property. All of the property along the Wissahickon Creek within city limits was attained by 1873.

3. Cornelius Weygandt, The Wissahickon Hills: Memories of Leisure Hours Out of Doors in the Old Countryside (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1930), 56.

4. Various newspaper articles, undated, unnamed, Jellet Clippings, Wissahickon Box 1, Germantown Historical Society.

5. Douglas MacFarlan and James Magee, ‘The Wissahickon Mills,” Vol. 2. Unpublished manuscript found in the secured history collection at the Free Library of Philadelphia, Logan Circle Branch. See also Wissahickon Turnpike Enactment, Act No 361, Session 1850, Approved 1856. Wissahickon Turnpike Authority and City of Philadelphia, Found in “General Wissahickon File,” Fairmount Park Commission Archives.

6. Linda F. McClelland, Presenting Nature: The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, 1916 to 1942 (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1993), 20–25; Galen Cranz, The Politics of Park Design (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1982), 19–24.

7. Various newspaper articles, undated, without names, Jellet Clippings, Wissahickon Box 1, and Wissahickon Box 2, Germantown Historical Society.

8. Pamphlet describing the history of the Friends of the Wissahickon, Friends of the Wissahickon Inc., Wissahickon Box 1 at the Gemantown Historical Society.

9. Joan Younger Dickinson, “Aspects of Italian Immigration to Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 90 (1966), 453.

10. Ibid.

11. Annual Report of the Chief Engineer, 1932, 1933. Fairmount Park Commission, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Fairmount Park Commission Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This report states that the work was done by men paid by George Woodward. A letter from Senator Woodward, President of Friends of the Wissahickon to Harry L. Hopkins, Chief Executive WPA, dated 9 November 1937, explains his contributions to Fairmount Park.

12. Annual Report of the Chief Engineer. Various years.

13. Annual Report of the Chief Engineer, 1935, 10–13, and 1936, 9–11. This list excludes a vast amount of the WPA work in the Wissahickon. They rebuilt dams, were responsible for extensive repairs of roads, trails, fences, and walls. A massive planting campaign also occurred, partially with the help of the Friends of the Wissahickon. Specific information on the planting work can be found in 1935: 40, 48–50, 52, and 1936: 32–33, 43–44, 40–41.

14. Annual Report of the Chief Engineer, 1931.

15. Cranz, 61–63.

16. Report by L.H. Weir referred to in the Transcript of Meeting on 16 November 1935, Fairmount Park Commission Investigation, in City Parks Association, Box 6, Urban Archives, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 7.

17. Actual expenditures from 1935–1942.

18. Archival research found nothing to determine the root of the idea for this project.

19. Official Project Application for Plans and Improvements of the Wissahickon Valley, WPA Project Folders, Official Project Number 465-23-2-310, Index 130 T935 & 936, Roll 5377, Reel 3136, National Archives, Washington DC.

20. Ibid.; “$834,000 Project started by the WPA along the Wissahickon,” Evening Bulletin 22 October 1937.

21. “Cool on Hot Dog Stands for Wissahickon” Evening Bulletin, 1 November 1937; “Hot Dog Stand Menace Looms in the Wissahickon” Philadelphia Inquirer, 11 November 1937.

22. Letter from Senator Woodward, President of Friends of the Wissahickon to Harry L. Hopkins, Chief Executive WPA, 9 November 1937, WPA State Files, Pennsylvania, 651.109 Parks and Playgrounds Construction and Improvements, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

23. Letter from Harry L. Hopkins, Chief Executive WPA to Senator Woodward, President of Friends of the Wissahickon, 15 November 1937, WPA State Files, Pennsylvania, 651.109 Parks and Playgrounds Construction and Improvements, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; “No Hot Dog Stands in the Wissahickon” Evening Bulletin, 12 November 1937; “The Gift Horse” Evening Bulletin, 12 November 1937.

24. Annual Report of the Chief Engineer. Various years.

25. Annual Report of the Chief Engineer, 1938.

26. Albert H. Good, Park Structures and Facilities (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1935).

27. Ibid., 3–4.

28. General descriptions of the plans are drawn from architecture drawings and on-site investigation.

Bibliography

“Bicycle Concession Building” (photograph). Evening Bulletin, 25 June 1940.

Brandt, Francis B. The Wissahickon Valley: Within the City of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Corn Exchange National Bank, 1927).

“Cool on Hot Dog Stands for Wissahickon.” Evening Bulletin, 1 November 1937.

Daly, T.A. The Wissahickon. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Garden Club of Philadelphia, 1922.

Dickinson, Joan Younger. “Aspects of Italian Immigration to Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography XC, October 1966, 445–65.

“$834,000 Project started by the WPA along the Wissahickon.” Evening Bulletin, 22 October 1937.

Germantown, Pennsylvania, Germantown Historical Society. Wissahickon, Box 1–3.

“The Gift Horse.” Evening Bulletin, 12 November 1937.

Good, Albert H., ed. Park Structures & Facilities. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1935.

MacFarlan, Douglas, and James Magee. “The Wissahickon Mills.” Unpublished Manuscript. Secured History Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia, Logan Circle Branch.

McClelland, Linda F.. Presenting Nature: The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, 1916 to 1942. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1993.

“Men & Things: Park Problems Arouse Citizen Concern: Letter to the Editor from W.S. Akon.” Evening Bulletin, 6 November 1937.

“Need Comfort Station.” Evening Bulletin, 22 June 1937.

“No Hot Dog Stands in the Wissahickon.” Evening Bulletin, 12 November 1937.

Palmer, Chris. Managing Director of Operations, Fairmount Park Commission (Former Wissahickon District Manager). Various Conversations, 1996– 2005.

“Park Body to Decide WPA Improvements.” Evening Bulletin, 17 November 1937.

“Park Conservation Urged: Trail Club Opposed to Hot Dog Sales In the Wissahickon.” Evening Bulletin, 20 November 1937.

“Park Stand Protested.” Evening Bulletin, 16 November 1937.

Philadelphia: Fairmount Park Commission Archives. Annual Report of the Chief Engineer (Also entitled: The Report of the Commissioners of Fairmount Park). Philadelphia: Fairmount Park Commission, 1929–1940.

Philadelphia: Fairmount Park Commission Archives. Files “Wissahickon Related,” “WPA: General,” “WPA: Wissahickon,” “Walnut Lane Golf Course,” and “Megargee Mill.”

Philadelphia: City Archives. “Fairmount Park Commission Appropriations and Expenditures, 1922–1951.”

Stainton, Ed, Head of the Structures Committee, Friends of the Wissahickon. Meeting about Rex Avenue Structure Roof. Various conversations 1996–2005.

Washington, D.C., National Archives. WPA Records. Project Folder “OP 465-23-2-310 General Wissahickon Improvements,” Index 130 T935 & 936, Roll 5377, Reel 3136.

Washington, D.C., National Archives. WPA Records. State File: Pennsylvania. “651.109 Parks and Playgrounds: Construction or Improvement.”

Weir, L.H. Parks: A Manual of Municipal and County Parks. New York: A.S. Barnes and Co., 1928.

Weygandt, Cornelius. The Wissahickon Hills: Memories of Leisure Hours Out of Doors in the Old Countryside, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1930.