Take Me Out to the Ball Park: The Restoration and Revitalization of Rickwood Field

David M. Brewer, Executive Director

Friends of Rickwood, Birmingham, Alabama

Note: This article originally appeared in the publication Preserve & Play.

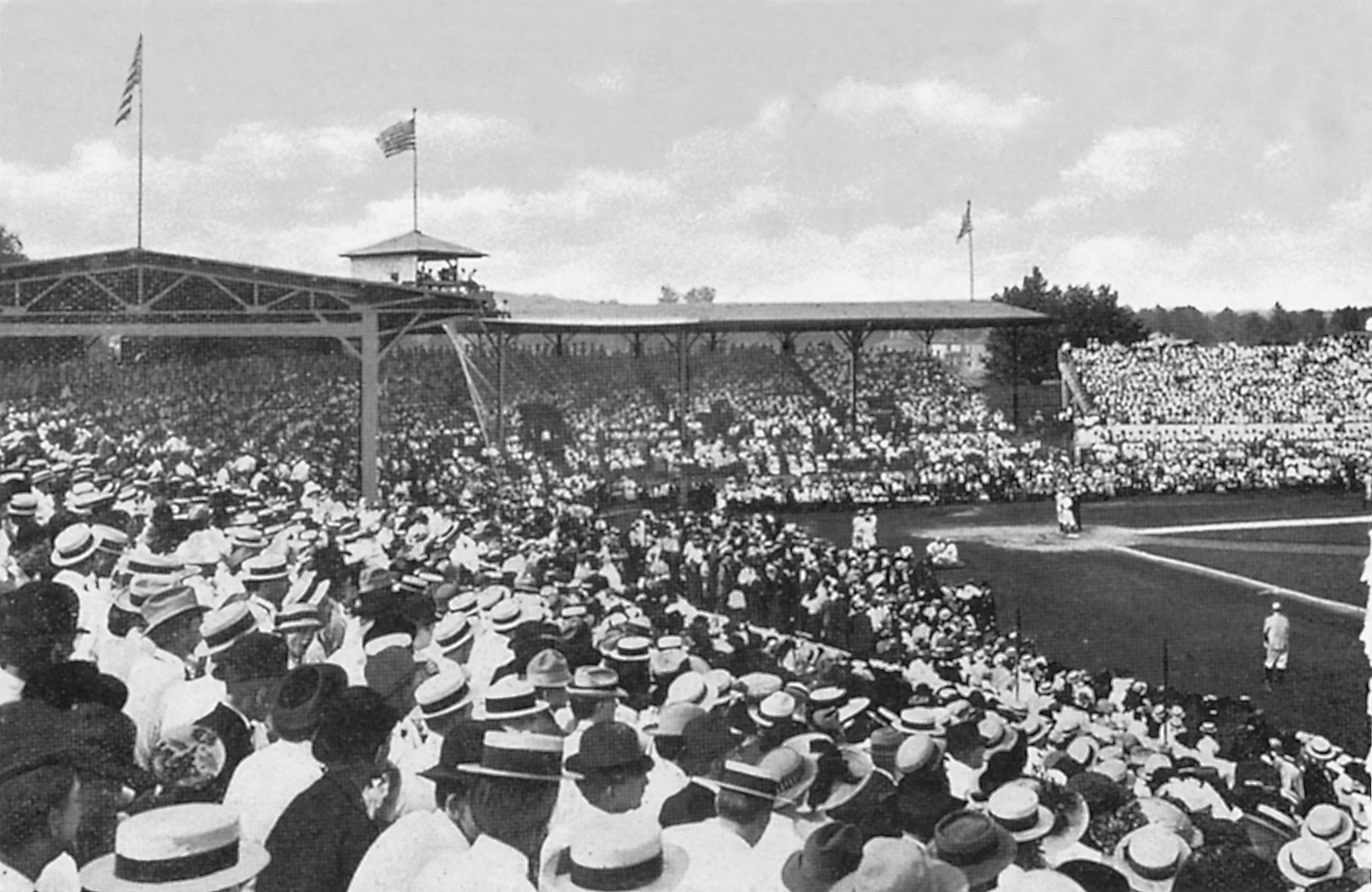

Birmingham baseball fans fill Rickwood Field, opening day, 18 August 1910. (Historic postcard, author’s collection)

Recognized by the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) as America’s oldest baseball park, Rickwood Field served as the home park for the Birmingham Barons from 1910 through 1987.(1) From 1920 through 1963, it also served as the home park of the Birmingham Black Barons, and is today recognized by the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum as one of only two remaining former Negro League ballparks.(2) Rickwood also frequently hosted games of traveling and barnstorming teams from the heyday of major league baseball, including more than fifty current members of the Baseball Hall of Fame.(3)

Rickwood Field, however, is more than just baseball. It is a key component of both local and national social fabric and collective history. During Rickwood’s heyday, going to your local baseball park to support the hometown team constituted a major social event and provided both a source of community pride and identity. In broader terms, the opportunity to witness the play of American cultural icons brought Birmingham and regional residents into the national fold and reassured them that they too shared a stake in the “great American pastime.”

Our nation and its game have changed dramatically during the past ninety-five years. Rickwood Field has witnessed and experienced many of these changes, yet today it remains as a reminder of a bygone chapter in our nation’s past. An unforgettable experience of mine helps to remind us why historic preservation remains a worthwhile endeavor. On a rainy March evening just before dusk, as I walked through the tunnel of the park and emerged onto the field, I suddenly became aware of an elderly gentleman sitting to my right, in the box seats behind first base. He had not spoken to me; I simply felt his presence. When our eyes met, he stood and adjusted the collar on his overcoat, and after pulling his hat down tight, he walked laboriously down the steps onto the field and extended his hand in an unspoken greeting. And then in a tone rich with emotion, he said “Son, this park is still just like I remember it.” At that moment, a gust of wind peeled-back the corner of the tarp covering the pitcher’s mound. When I had replaced the weight on the tarp and turned back around to face the dugout, he was no longer standing there. After making one more pass through the grandstands, I locked the gate and began my drive home. Later that evening, I thought more about what he had said . . . “this park is still just like I remember it.” In those few heartfelt words, he had given value to everything that we are doing at Rickwood Field. Not the Friends of Rickwood alone, but the entire Birmingham community, and every visitor and ball player that steps through the gate. A true labor of love, we are together keeping one of America’s treasures alive.(4)

If the “why” of restoring and revitalizing an old ball park seems obvious, the “how” remains a bit more elusive. By pursuing a multi-tiered strategy defined in the Rickwood Master Plan, the Friends of Rickwood has established itself as an effective steward of this American treasure and has successfully completed more than a dozen renovation component projects, consisting of upgrades to the facility, field, and grounds.5Central to the comprehensive revitalization of the park is its continued role as a high profile baseball venue, buttressed by the marketing of the park as a dynamic destination and living history museum.

It is my hope that information presented herein will illuminate both the “why” and the “how” of the equation, through an examination of the strategies and challenges integral to this ongoing project. This overview will also propose that the restoration and revitalization of Rickwood Field can serve as a model for similar endeavors, while not ignoring the notion that preservation success may be fleeting. And although we frequently talk in terms of having “saved” the park, in reality the project remains ongoing, with many challenges still ahead.

Okay, So Why Save an Old Baseball Park?

When talking about any preservation project, the obvious place to start is “why?” In the case of Rickwood Field, the question is specifically, “why invest in an old baseball park?” We think that there are a number of compelling reasons:

- HABS status as America’s oldest baseball park—there is only one “oldest” anything, and we believe that this National Park Service (NPS) recognition adds tremendous credibility to our project

- the park’s rich baseball history

- the park’s role in community and national social fabric, including the Civil Rights story

- the park’s architectural significance

- the park’s potential role as a catalyst for community revitalization

In August 1993 the NPS Historic American Building Survey completed its Rickwood Field documentation project, and concluded that Rickwood Field is the nation’s oldest surviving baseball grandstand on its original site, thereby qualifying it as America’s oldest baseball park.(6) There are of course many other great old parks, and not infrequently, we receive comments about a particular park being a challenger to this status. But, to date, no challenger’s claims have been substantiated. In each case thus far, it has proven to be an earlier piece of real estate occupied by a later grandstand.(7)

A capacity crowd fills Rickwood Field in 1929. (Glynn West)

Rickwood’s role as host for the Barons and their Southern Association and later Southern League rivals, the Black Barons and their Negro League counterparts, and the frequent play of Major League teams further supports the preservation argument. The park’s first six decades produced an impressive list of alumni, including baseball legends Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Jackie Robinson, Ted Williams, Willie Mays, Joe DiMaggio, Satchel Paige, Dizzy Dean, Hank Aaron, Honus Wagner, Rube Foster, Rogers Hornsby, Cool Papa Bell, Lou Gehrig, Stan Musial, Ernie Banks, Reggie Jackson, and many others.(8) And although the Black Barons concluded their last season in 1963, and the Barons left for the suburbs in 1987, baseball continues today to be alive and well at Rickwood, with approximately 200 games played annually.

Paralleling the park’s baseball legacy is its role in Birmingham and American social history. Erected in 1910, Rickwood Field exemplifies the enthusiasm and optimism of early twentieth century America, a nation transitioning from a rural agrarian society to that of an urban industrialized society. A.H. “Rick” Woodward, son of a wealthy Birmingham industrialist and builder of Rickwood Field, typified the enthusiasm and boosterism of early twentieth century America, and specifically the young city of Birmingham, the rising industrial center of the New South.(9) As industry established itself in Birmingham, neighborhoods and communities sprouted around the plants, mills, and mines of this blue collar, working class town.

The economic and social transition that accompanied this growth, however, brought profound changes to everyday life. The new industrial worker found himself faced with a much more regimented and much less autonomous lifestyle, including a growing domination by the company and the time clock. As industrial life became more arduous, employers instituted programs designed to boost both morale and productivity. The introduction of company-sponsored recreation programs, such as baseball teams, became commonplace, with Birmingham firms large and small fielding competitive baseball squads. Baseball in general, and Rickwood Field specifically, became a core component of Birmingham’s working class industrial identity.

The high caliber of play among many of these company-sponsored teams set the precedent for professional baseball in Birmingham. Ultimately, both the Barons and Black Barons tracked and recruited local talent from this rich pool. As this talent feeder system developed, fan loyalty toward individual company squads soon evolved into a passionate following for Birmingham’s professional baseball teams.

In the broader view of Birmingham civic pride, Rickwood became the focal point of community identity. And although segregation statutes prevented black and white fans from socializing together at Rickwood Field, both groups packed the grandstands to cheer on their respective teams and heroes. Moreover, due to the Barons’ and Black Barons’ shared use of the park, Rickwood occupies a place in our community’s and nation’s civil rights story, a place recently acknowledged by its inclusion in the National Trust’s “African American Historic Places Initiative.”(10)

Rickwood Field’s distinctive front entry (Bill Chapman)

In architectural terms, Rickwood Field represents classic early twentieth century ballpark design and is considered to be the first minor league stadium built of concrete and steel.(11) The grandstand, coupled with a 1928 Mission Style entrywayand 1936 field light towers, forms the core of the park. While researching ball park design, Rick Woodward enlisted the assistance of legendary baseball icon Connie Mack in the building of Rickwood, resulting in a park fashioned after Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field and Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, and referred to at the time as “The South’s Finest Base Ball Park.”(12) Today, Rickwood remains a prime example of a second generation American ballpark design, a style that replaced the earlier wooden grandstands. This era of ballparks offered greater fan comfort and amenities while retaining the human scale lost in the later generation of larger, more grandiose modern baseball stadiums.

Reflecting this combination of sports history, social history, and history of the built environment, Baseball America magazine ranked Rickwood Field as one of the top five minor league ballparks of the twentieth century in terms of “significance beyond their cities.” And in an analysis of ballparks old and new, Baseball America editors wrote that “the history of Rickwood Field . . . speaks for itself,” with the park’s significance continuing “to stand the test of time.”(13) Ultimately, however, the preservation case must be made not only in cultural and historical terms, but also in economic terms.

Barons ballplayers and fans pose in front of Rickwood’s distinctive entrance, 1930. (Chuck Stewart)

To that end, we cite the approximately 20,000 annual visitors to Rickwood, many of whom stay the night in Birmingham and spend their money at local hotels, restaurants, and entertainment venues. Moreover, a revitalized Rickwood Field is serving as a catalyst for the reinvestment and redevelopment of not only the neighborhood surrounding the park, but also Birmingham’s larger West End community. National media exposure for the park, including Rickwood’s portrayal as one of Birmingham’s numerous cultural and historic attractions, has direct economic implications for the city’s heritage tourism and entertainment industries.(14) However, as we continue to make the pitch for Rickwood’s on-going revitalization, the bottom line remains, “how do we go about achieving our objective of comprehensive revitalization of the park?”

A brief examination of the organization’s background sheds light on this central challenge. The Friends of Rickwood, a 501(c)3 non-profit organization formed in 1992, is a true grassroots organization with one full-time employee, a Board of Directors, and roughly 500 members. The group’s diverse board and membership, consisting of preservationists, baseball purists, and community members, is committed to keeping alive this unique piece of Americana. To date, approximately $2 million in renovation to the park has been completed, highlighting the broad support for the project and the tenacity of the organization, including its ability to establish goals and see them to fruition.(15)

The Strategy

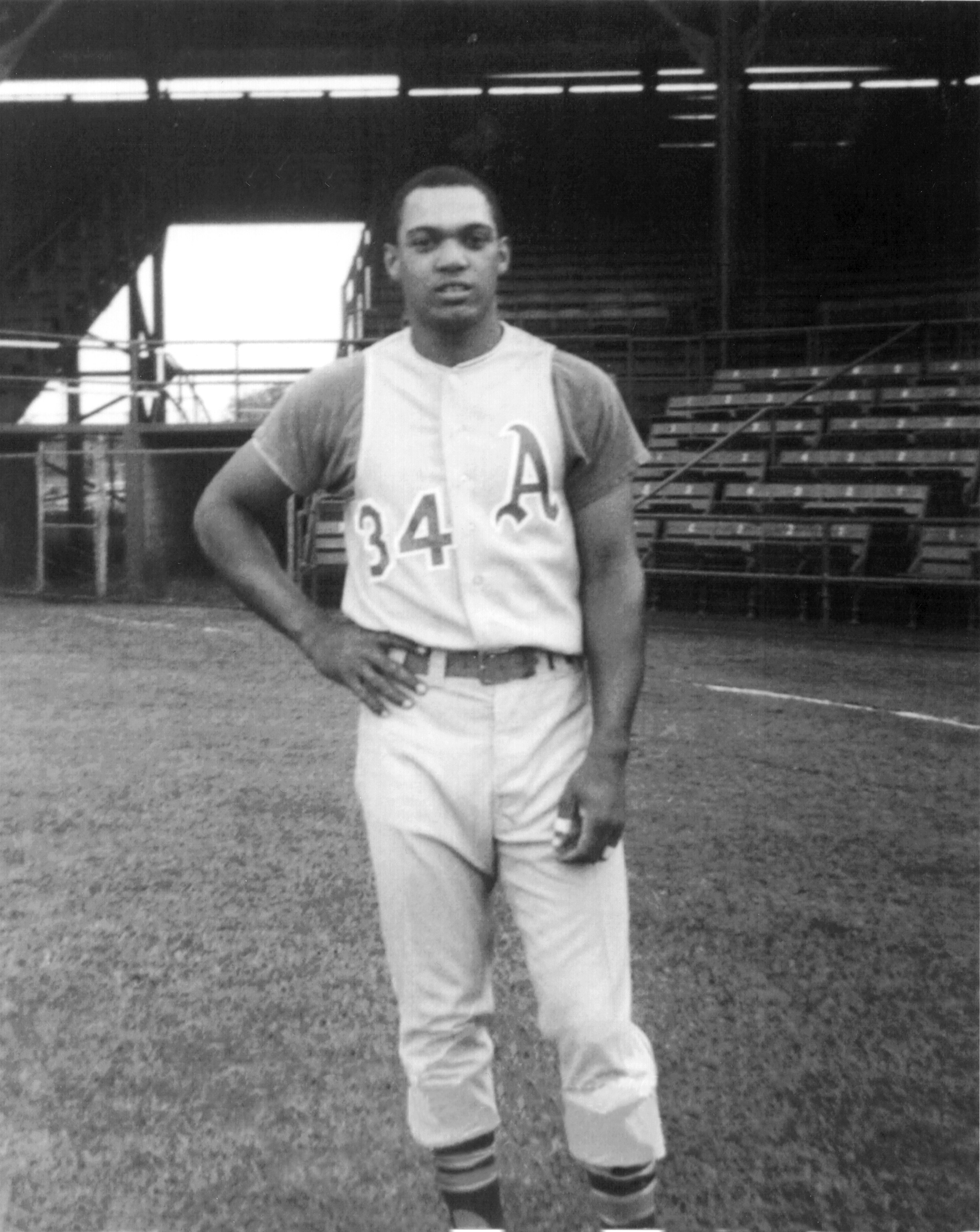

Seventeen-year-old Black Baron Willie Mays, with Rickwood right field in backgound, 1948 (T.H. Hayes Collection, Memphis Shelby Public Library)

The total revitalization of Rickwood Field includes the ongoing marketing of the park as a competitive baseball venue. Our game schedule has averaged approximately 200 baseball games per year in each of the past eight years, including the play of the Birmingham Board of Education’s high school baseball program, the Birmingham Police Athletic League, numerous men’s amateur leagues, college and junior college ball, and the hosting of tournaments and showcase events. This range of activities highlights the park’s role in providing recreational opportunities across a broad demographic range. The Rickwood Classic, the annual turn-back-the-clock high profile fundraising event, also continues to bring the Birmingham Barons back to their old home park, generating both significant revenue and invaluable media exposure.

The marketing of the park as a key component of the local and regional historic site community, as well as a living-history tourist destination, is also ongoing. Toward this end, the Friends of Rickwood has in the past several years more aggressively pursued an educational and tourism path using a combination of means. Efforts have included launching a revised Rickwood Field web site, and design and production of a new multi-page marketing brochure, as well as a new “rack” brochure. The latter, funded in part by the Alabama Bureau of Tourism and Travel, is now available to the traveling public through the state’s brochure distribution program.(16) The City of Birmingham, the Birmingham Regional Chamber of Commerce, and the Birmingham Convention and Visitor’s Bureau have also been instrumental in marketing efforts. Inclusion in several recently published travel guides, as well as a presence on numerous ball park and heritage travel web sites, highlights our tourism and educational marketing campaign.(17)

On-site efforts include the creation of the “Rickwood Self-Guided Tour,” designed to address “walk-up” visitors to the park. Moreover, we continue to host field trips and student groups of all ages, emphasizing further Rickwood’s function as an educational site. This multi-tiered marketing approach has proven successful, so much so that Rickwood Field was recently listed by USA Today newspaper as one of the “10 great places to touch base with the best.”(18) Despite this success, funding remains the key ingredient, bringing us to the core of the “how” component.

Birmingham A’s Reggie Jackson at Rickwood Field, 1967 (Buddy Coker)

Fortunately, the revenue stream originates from several sources, including a mix of public and private funds, leaving us not solely dependent upon a single revenue source. Rickwood Field is currently a line item in the city of Birmingham’s annual budget, but is not funded fully in the same manner as other city-owned sites. Our line item status not withstanding, the city’s supportive role, both financial and emotional, is invaluable. Other public funds have come through grants from the state, including the Alabama Historical Commission, the Alabama Bureau of Tourism and Travel, the Alabama Department of Community Affairs, and the Alabama State Park’s Joint Study Committee.

Private sources also continue to account for a significant portion of funding, including the crucial support of the foundation community. The Birmingham business community has been extremely supportive, with a 1993 corporate campaign raising considerable funds. In addition to cash pledges, Birmingham businesses and firms have contributed generously with in-kind services and expertise.

Facility rentals generate essential revenue, along with a modest addition generated from merchandise sales. Individual contributions remain an invaluable funding source, as does the aforementioned Rickwood Classic, which continues to produce a profit each year. The Friends organization has also been successful in marketing the park as a ready-made vintage baseball set for photo shoots, commercials, and movies, all of which generate revenue as well as increased visibility.(19)

Rickwood Classic action, Barons versus Montgomery, 2005 (Christopher Frey)

But despite our success to date, many challenges lie ahead, with funding remaining the biggest issue. Rickwood’s status in the city’s budget is precarious at best, and requires a renewal of the relationship each fiscal year. Grant funds and corporate support are also becoming increasingly competitive. Recruiting “new blood” into the organization and project is also an ongoing challenge, as is developing a relationship with the younger generation that ultimately will have to “take over the reins.” Keeping the project in the media spotlight also continues to be a formidable task. At the core of all of these challenges, however, is the realization that a ninety-five year old facility requires almost constant attention and care. The park’s mechanical systems are old and outdated, and will require extensive upgrades in the near future. Exposure to weather and climate is taking its toll on the physical structure, with the need for extensive stabilization and repair to the concrete becoming more acute.

Accompanying these mounting challenges, however, is the growing relevance of saving the park, and Rickwood’s role as a potential model for similar public-private efforts in other cities. Preservation and revitalization efforts are being considered or are ongoing in various stages at numerous other historic baseball parks, including several examples involving grassroots “Friends” type organizations working with community members to save local parks.(20) Other communities have pursued for-profit paths and view minor league and independent league baseball and the modernization of their facilities as salvation. The growing trend toward building new parks with a vintage look and feel further reinforces the relevance of preserving and revitalizing the classic ball yards of yesterday.

Middle school students visiting Rickwood Field as part of their Civil Rights study (Friends of Rickwood)

Whatever the case, it is our hope that the revitalization of Rickwood Field may in some way assist other communities in their baseball park preservation and restoration projects. Our approach is of course not fail-proof, nor does it fit every case, and each day presents new challenges. While the success enjoyed to date by Friends of Rickwood certainly does not provide all of the answers, hopefully it helps reveal some of the questions.

In conclusion, I’d like to quote briefly a true friend of Rickwood Field, Donnie Harris, former Black Baron centerfielder. In response to a question concerning Rickwood’s relevance in the new-park-versus-old-park argument, Donnie replied simply, “You can have those new fields with artificial turf and sky boxes. This is a ballpark. You need the sun and wind in your face. To me, Rickwood is a one-of-a-kind place.” We concur, and look forward to many more years of baseball and community pride at Rickwood Field.

Employed since 1998 as the Executive Director of the Friends of Rickwood, David M. Brewer has served as the primary coordinator for the restoration and revitalization of Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama. He holds a Master of Arts in History from the University of Alabama at Birmingham with a focus on American social history and historic preservation, and with specific interest in the development and history of the Birmingham Industrial District.

This article originally appeared in Preserve and Play.

Notes

1. National Park Service, HABS Report # AL-897, “Rickwood Field,” 1993, 2.

2. Statement by Raymond Doswell, Curator, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, quoted in article on Hinchliffe Stadium (Patterson, NJ), by Steve Strunsky, accessible at http://www.nlbm.com/ns/NewsDetail.cfm?NewsID=69.

3. For a partial list of Rickwood veterans who are Hall of Fame members, see Timothy Whitt, Bases Loaded With History: The Story of Rickwood Field (Birmingham, Alabama: R. Boozer Press, 1995), 103.

4. Recount of this experience first published in the Friends of Rickwood newsletter, Out of the Park 3, Spring 2001.

5. Rickwood Field Master Plan, by Davis Speake & Associates (now Davis Architects), 1993.

6. HABS Report, 2.

7. For example, Warren Ballpark in Bisbee, Arizona.

8. Birmingham newspapers during the period covered extensively the play of both the Barons and Black Barons, and contain references to these, and many other, legendary ball players.

9. For a discussion of Birmingham as a New South industrial center, see W. David Lewis, Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham Industrial District: An Industrial Epic (Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1994).

10. “National Trust’s African American Historic Places Initiative: An Update,” 23 June 2004.

11. HABS Report, 3; Michael Benson, Ballparks of North America: A Comprehensive Historical Reference to Baseball Grounds, Yards, and Stadiums, 1845 to Present (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1989), 33.

12. Whitt, Bases Loaded With History, 21–22; caption from 1930s Rickwood Field postcard, Birmingham View Company.

13. Baseball America 19, no. 3 (15 November 1999), 50; Ibid. 23, no. 26 (22 December 2003), 39.

14. For example, HGTV, “Restore America,” April 2000; Turner South, “Three Day Weekend,” June 2004; Turner South, “Blue Ribbon Ballparks,” April 2005.

15. Component projects completed to date include the replacement of the original drop-in scoreboard, the installation of a new public address system, the rebuilding of a vintage-style gazebo press box as well as the building of a modern grandstand press box, the restoration of the distinctive front entry building as well as the repainting of the park’s entire exterior, improvements to the playing field, the reproduction of vintage style outfield billboards, the replacement of portions of the grandstand roof and the placement and painting of additional structural support columns, the renovation of the main men’s and women’s restrooms, and the renovation of the visiting team and home team locker rooms. Relationships with similar organizations have added credibility to the project and include the National Park Service, National Trust for Historic Preservation, Alabama Historical Commission, Jefferson County Historical Commission, Birmingham Historical Society, Alabama Negro League Players Association, Society of American Baseball Researchers, International Association of Sports Museums and Halls of Fame, and the Alabama Museums Association.

16. Rickwood Field web address: www.rickwood.com

17. For examples of references to Rickwood Field in recent travel guides, see Chris Epting, Roadside Baseball: Uncovering Hidden Treasures From Our National Pastime (St. Louis, Missouri: Sporting News, 2003), 107; and Jim Carrier, A Traveler’s Guide to the Civil Rights Movement (New York and London: Harcourt, Inc., 2003), 224.

18. USA Today, 8 April 2005.

19. Feature length films shot in-part at Rickwood include Cobb and Soul of the Game; numerous television commercials and print ads have also been shot at Rickwood.

20. Historic parks that have attracted the attention of preservationists include, among others, Durham Athletic Park (Durham, North Carolina), Bossie Field (Evansville, Indiana), Engel Field (Chattanooga, Tennessee), League Park (Cleveland, Ohio), Luther Williams Field (Macon, Georgia), Hinchliffe Stadium (Paterson, New Jersey), Bush Stadium (Indianapolis, Indiana), War Memorial Stadium (Greensboro, North Carolina), and Gill Stadium (Manchester, New Hampshire).